When the Second World War ended in Europe, in May 1945, the Allied governments were faced with a problem. Undoubtedly, the German Nazi party had committed crimes on a continental scale, and common justice demanded that there should be retribution.

What form should this retribution take? Germany had been punished severely after the First World War by the Treaty of Versailles. The victorious statesmen of the time had decided to take revenge. In the words of a British cabinet minister, they would "squeeze the German lemon until the pips squeak". It had not worked. Although the Kaiser had abdicated, German society stayed very much the same. The Treaty imposed real hardships on the German people, but their leaders were untouched. The autocracy at the heart of Germany remained.

There had been an attempt at prosecuting war criminals. A trial was held in Leipzig in 1921, in a German court. Not surprisingly, it degenerated into a farce and was quietly terminated without result. The old attitudes and Prussian militarism survived to fight another day.

What form should this retribution take? Germany had been punished severely after the First World War by the Treaty of Versailles. The victorious statesmen of the time had decided to take revenge. In the words of a British cabinet minister, they would "squeeze the German lemon until the pips squeak". It had not worked. Although the Kaiser had abdicated, German society stayed very much the same. The Treaty imposed real hardships on the German people, but their leaders were untouched. The autocracy at the heart of Germany remained.

There had been an attempt at prosecuting war criminals. A trial was held in Leipzig in 1921, in a German court. Not surprisingly, it degenerated into a farce and was quietly terminated without result. The old attitudes and Prussian militarism survived to fight another day.

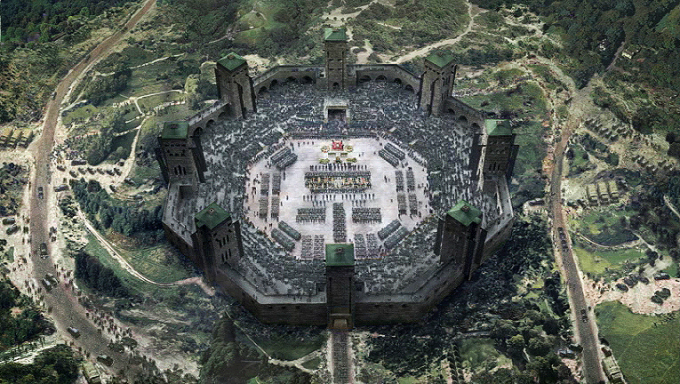

The massive and oppressive monument in East Prussia to Germany's war dead,

on the occasion of President Hindenberg's funeral - nothing has changed.

on the occasion of President Hindenberg's funeral - nothing has changed.

When the guns fell silent in Europe in 1945, Allied were resolute. This time things would be different. Germany and its people would not be punished, but its criminal leadership would be. They would be given a fair trial in front of the world and either be found not guilty, or they would be punished severely. The Allies set up the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg and tried 22 Nazi leaders.

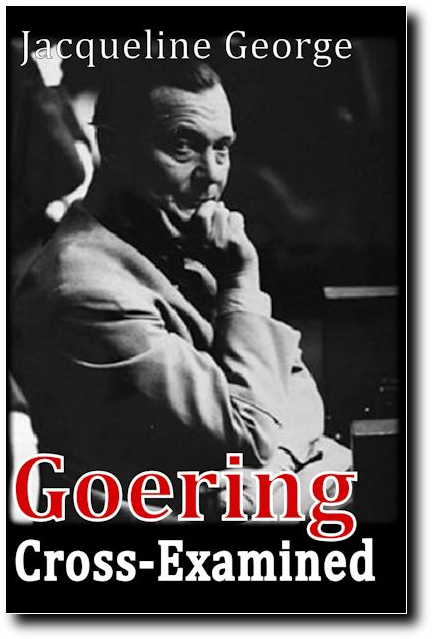

Who would appear before the Tribunal? Of the top Nazis, Hitler, Goebbels, Himmler and Bormann were already dead. Only 22 men stood trial and nearly all of them impressed observers only by their ordinariness. Hermann Goering stood out head and shoulders above the crowd. The senior Field Marshal, Deputy Führer and commander of the Luftwaffe, dominated the other defendants and, given half a chance, would dominate the courtroom as well.

Who would appear before the Tribunal? Of the top Nazis, Hitler, Goebbels, Himmler and Bormann were already dead. Only 22 men stood trial and nearly all of them impressed observers only by their ordinariness. Hermann Goering stood out head and shoulders above the crowd. The senior Field Marshal, Deputy Führer and commander of the Luftwaffe, dominated the other defendants and, given half a chance, would dominate the courtroom as well.

Hermann Goering on trial at Nuremberg

Goering entered the witness stand to give his account of the Third Reich and his place in it. He was charismatic and quick witted. It was clear he felt he deserved respect if not affection, and his testimony came from a leader of a great nation in turbulent times.

Now it was the task of the prosecutors to tear through the façade he had painted and lay his crimes bare for all to see. The lead prosecutor, Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson began the cross-examination and soon found himself pitted against a very wily opponent. In what has been labelled as the worst cross-examination in history, Goering was left virtually untouched. It was then the turn of Jackson's colleague Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe to try and open Goering's crimes to public scrutiny.

The story of the three men - Goering, Jackson and Maxwell-Fyfe - makes gripping reading. Exact court transcripts are reproduced here so the reader can follow the struggle day by day, and look into the character of the man who was Hermann Goering.

Now it was the task of the prosecutors to tear through the façade he had painted and lay his crimes bare for all to see. The lead prosecutor, Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson began the cross-examination and soon found himself pitted against a very wily opponent. In what has been labelled as the worst cross-examination in history, Goering was left virtually untouched. It was then the turn of Jackson's colleague Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe to try and open Goering's crimes to public scrutiny.

The story of the three men - Goering, Jackson and Maxwell-Fyfe - makes gripping reading. Exact court transcripts are reproduced here so the reader can follow the struggle day by day, and look into the character of the man who was Hermann Goering.

Review

This very readable book brings together the many strands of the Goering war crimes trial in a way that allows the interested but legally challenged reader to appreciate the hubris and depravity of the Reich's Deputy Führer.

The reader is left with the impression that Goering, throughout his trial, believed in the righteousness of the Nazi Cause and was surprised and disappointed in the final outcome. Goering's testimony to the Tribunal is both chilling and a fitting final testimony to the Nazi era.

~ Charles Gillman-Wells

This very readable book brings together the many strands of the Goering war crimes trial in a way that allows the interested but legally challenged reader to appreciate the hubris and depravity of the Reich's Deputy Führer.

The reader is left with the impression that Goering, throughout his trial, believed in the righteousness of the Nazi Cause and was surprised and disappointed in the final outcome. Goering's testimony to the Tribunal is both chilling and a fitting final testimony to the Nazi era.

~ Charles Gillman-Wells